Today we’re going to look at the ‘Circle of Fifths’. You may have come across the term before, or the ‘Circle of Fourths’, or just ‘The Circle’.

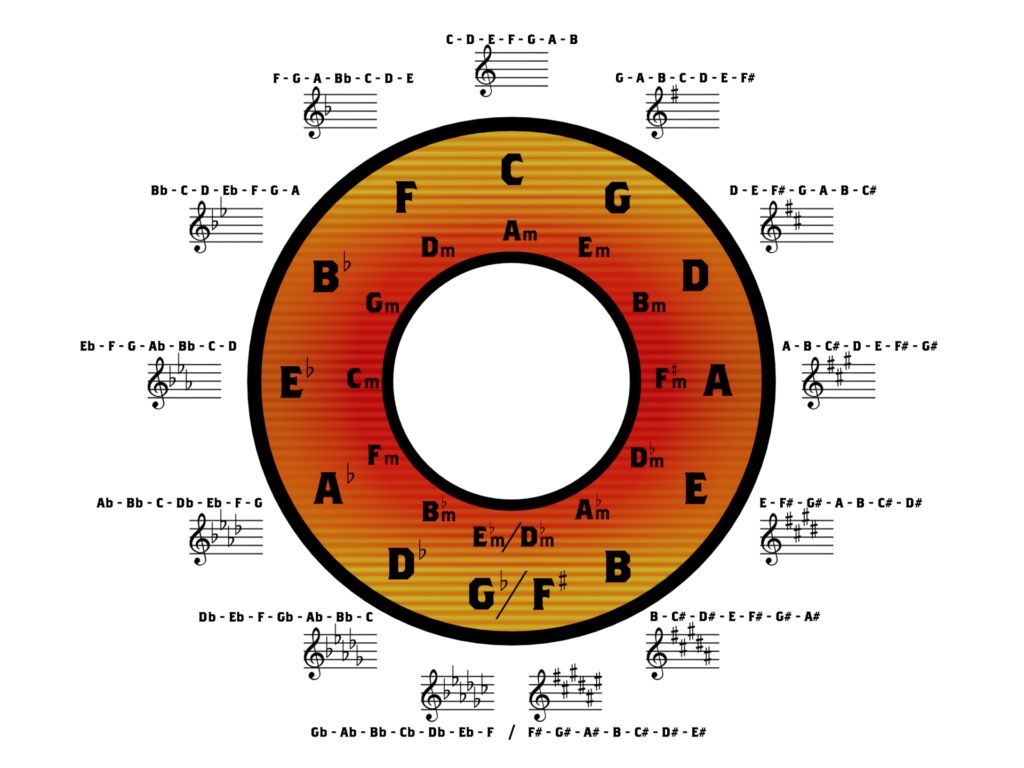

Check out the diagram below and then we’ll look at what it means and why its useful.

As you can see if we move clockwise in The Circle of Fifths we go up in fifths, e.g. C to G. If we move anti-clockwise we go up in fourths, e.g. C to F. The inner ring shows the relative minor key of each Major key. For example the relative minor to C Maj is Am. The relative minor of G Maj is Em etc.

Some people prefer to learn the circle in fourths and some prefer fifths. It helps to learn both ways but we’ll look at fifths today.

We’ll start with the key of C major and move through every key, going up a fifth each time. C has no sharps (#) or flats (b). The next key, a fifth higher is G major, this has one sharp, F#. The next key is D Major which has two sharps, F# and C#.

Note that each new key has the same notes but the fourth of the previous key is raised by a semi-tone. If we look at C on the circle we can see that G is the next key and the note that is raised would be F, which is before C on the circle.

Memorizing The Circle of Fifths

An easy way to remember the order of notes is to learn the first 2 notes, C and G. Every other note is a whole-tone higher. A tone above C is D so we get C, G, D. A tone above G is A, so we get C, G, D, A and so on:

C, G, D, A, E, B, F#, Db, Ab, Eb, Bb, F, C.

Remember that a tone above B is C#, which can also be named Db. I move to the ‘flat’ naming of the notes once I get beyond the key of F# Major…

F#/Gb

When we get to F# there are six #’s:

F#, G#, A#, B, C#, D#, E#.

The seventh is the note ‘E#’, technically there is no such note, it is actually the note ‘F’. However if we use F we get two F notes, F and F# and no E. What we want is one of each letter, so we write E# instead of F.

The reason for this is to do with traditional musical notation. Each key signature has # or b symbols on the appropriate line of the stave. You can see the key signatures next to each note on the circle.

If we use flats instead of sharps for F# major we would call it Gb Major. The notes would be:

Gb, Ab, Bb, Cb, Db, Eb, F.

Now we avoid the need for the E# which has become F but we now have a Cb instead of B.

The need to name the notes in this way is only true for F#/Gb due to the six sharps or flats. The next key in the circle is Db which has five flats:

Db, Eb, F, Gb, Ab, Bb, C.

It makes sense to use b’s instead of #’s because if we call the key C# we get:

C#, D#, E#, F#, G#, A#, B#.

Since B# and E# don’t technically exist it is better to call the key Db so that the E# becomes F and the B# becomes C.

Sharpening a flat

When we move beyond Gb we are still raising the fourth note of the previous key by making it sharp, however in Gb the fourth is Cb, if we make this sharp we get C natural. So by continuing, instead of getting more sharp notes we get fewer flat notes in each new key. This will make more sense when you look at the notes of each key:

C – D – E – F – G – A – B – C

G – A – B – C – D – E – F# – G

D – E – F# – G – A – B – C# – D

A – B – C# – D – E – F# – G# – A

E – F# – G# – A – B – C# – D# – E

B – C# – D# – E – F# – G# – A# – B

F# – G# – A# – B – C# – D# – E# – F#

Db – Eb – F – Gb – Ab – Bb – C – Db

Ab – Bb – C – Db – Eb – F – G – Ab

Eb – F – G – Ab – Bb – C – D – Eb

Bb – C – D – Eb – F – G – A – Bb

F – G – A – Bb – C – D – E – F

What the Circle tells us

The circle gives us quite a bit of useful information so its a handy diagram to have. We can see which notes are in a key by looking at the notes before and after on the diagram. Pay attention to the inner circle too which shows the relative minor.

If you look at D Major, the note before is the 4th (G), the note after is the 5th (A), the “inner” note is the 6th (B) and also the root of the relative minor, the note before this is the 2nd (E) and the one after is the 3rd (F#). So you can quickly see all the notes, except the 7th from the diagram . The 7th is simple a semitone before the root in a Major key (C# in relation to D). You will also notice that all the notes on the “inner” circle are minor chords and the ones on the outer circle are Major chords. So in relation to D we get:

DMaj, Em, F#m, GMaj, AMaj, Bm.

Then you just have to remember that the 7th is a semitone below the root and is always a diminished triad. In relation to D this would be C# diminished.

Each Key is closely related to the ones next to it. C Major is closely related to A minor, they have all the same notes. G Major and F Major are also next to C on the diagram and they have only one note different between themselves and C Major.

This shows us that we can easily move from C Major to Am, FMaj or GMaj, or even the relative minor scales of F and G.

By looking at the opposite side of the diagram you can see which key has the least amount of notes in common with the key you are in. For C Major the Key on the opposite side is F# Major which has the least number of common notes with C Major.

Final Thoughts

Now that you are aware of the Circle of fifths diagram and what it shows you can start to make use of it in your writing. Next time you want to change keys for example you can use the diagram to see which keys are closest to the one you’re in. You can also easily move through multiple keys to the one you want by going up in either fourths or fifths.

Try keeping a copy of the Circle nearby next time you write a song and see if it helps inspire you to try new things!

No Comment